Artist's Books / Special Editions

Almond, Darren: All Things Pass

Almond, Darren / Blechen, Carl: Landscapes

Brown, Glenn: And Thus We Existed

Butzer, André: Exhibitions Galerie Max Hetzler 2003–2022

Chinese Painting from No Name to Abstraction: Collection Ralf Laier

Choi, Cody: Mr. Hard Mix Master. Noblesse Hybridige

Demester, Jérémy: Fire Walk With Me

Dienst, Rolf-Gunter: Frühe Bilder und Gouachen

Dupuy-Spencer, Celeste: Fire But the Clouds Never Hung So Low Before

Ecker, Bogomir: You’re NeverAlone

Elmgreen and Dragset: After Dark

Förg, Günther: Forty Drawings 1993

Förg, Günther: Works from the Friedrichs Collection

Galerie Max Hetzler: Remember Everything

Galerie Max Hetzler: 1994–2003

Gréaud, Loris: Ladi Rogeurs Sir Loudrage Glorius Read

Grosse, Katharina: Spectrum without Traces

Hatoum, Mona (Kunstmuseum

St. Gallen)

Eric Hattan Works. Werke Œuvres 1979–2015

Hattan, Eric: Niemand ist mehr da

Herrera, Arturo: Boy and Dwarf

Hilliard, John: Accident and Design

Horn, Rebecca / Hayden Chisholm: Music for Rebecca Horn's installations

Horn, Rebecca: 10 Werke / 20 Postkarten – 10 Works / 20 Postcards

Huang Rui: Actual Space, Virtual Space

Kowski, Uwe: Paintings and Watercolors

Mikhailov, Boris: Temptation of Life

Mosebach, Martin / Rebecca Horn: Das Lamm (The Lamb)

Neto, Ernesto: From Sebastian to Olivia

Oehlen, Albert: Mirror Paintings

Oehlen, Albert: Spiegelbilder. Mirror Paintings 1982–1990

Oehlen, Albert: unverständliche braune Bilder

Oehlen, Pendleton, Pope.L, Sillman

Oehlen, Albert | Schnabel, Julian

Phillips, Richard: Early Works on Paper

Riley, Bridget: Paintings and Related Works 1983–2010

Riley, Bridget: The Stripe Paintings

Riley, Bridget: Paintings 1984–2020

Roth, Dieter & Iannone, Dorothy

True Stories: A Show Related to an Era – The Eighties

Wang, Jiajia: Elegant, Circular, Timeless

Wool, Christopher: Westtexaspsychosculpture

Zhang Wei / Wang Luyan: A Conversation with Jia Wei

|

|

|||

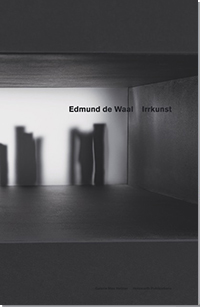

Edmund de Waal:

Irrkunst English / German |

Porcelain is the passion of English artist Edmund de Waal (*1964). He creates delicate vessels and shards that he places in vitrines intricately designed for the purpose. The porcelain pieces are charged with the sensibility of their making, hard as stone yet extremely fragile. Alone or in groups, they become protagonists in a dialog between remembrance and archived history. For his exhibition at both venues of Galerie Max Hetzler in Berlin, de Waal followed the spirit of Walter Benjamin, whose writings had rst introduced the artist to the city. The title, Irrkunst, goes back to Benjamin’s concept of an art of getting lost. In the exhibition spaces in Bleibtreustraße – you can see Benjamin’s former school from the winter garden – de Waal’s works refer to the author’s childhood and his passion for collecting and archiving things as a form of remembrance. Meanwhile the spaces in Goethestraße – a former post office – are suffused with both a sense of loss and departure. Here the work that lends the exhibition its title looms like a dark barrier cutting through the room, a powerful behemoth overshadowing the lives of the porcelain objects. A luminous library with writings by and about Benjamin, a large table, stationery, and a historic map of Berlin offers a space for writing down the experience and drawing up plans. This publication brings together all works from the exhibition and thus itself becomes an archival object for the exchange of different experiences.

IRRKUNST (excerpt from the text by Edmund de Waal) I work with things. I make them, from porcelain. And then I arrange them, find places to put them down, on shelves or within vitrines, in houses and galleries and museums, move them around so that they are in light or in shadow. They are installations, or groupings, or a kind of poetry. They have titles, a phrase or a line that helps them on their way in the world. And I write about things too, try to give objects the attention that I think they deserve. Those writers who care about this world of things matter to me very much. There are not many. For thirty years I have loved the work of Walter Benjamin, the writer and philosopher and collector. He believed in mapping the world through objects: he collected amongst many other things children’s toys, postcards, postage stamps and books, putting things into visitors’ hands, musing over them ‘like a pianist improvising at the keyboard’. He describes the pleasures of opening packing cases of his library and feeling reconnected to his books after many years. His great and obsessive, unfinished work on Paris, The Arcades Project, is an attempt to recreate the city through encounters with its material life. This is my first exhibition in Berlin. It is a city I know best through the writing of Walter Benjamin, a city I am coming to know through walking and retracing particular journeys. Walking is many things. It is a way of thinking: walking alone is always walking in conversation. Benjamin was born here in 1892 and though as a Jewish writer he was forced into exile, leaving to live on the Danish coast, on Ibiza, in Paris, Berlin remains his city. He was also a walker and writes that there is an art to getting lost, Irrkunst: the art of noticing what has been disregarded. Benjamin says that he had ‘a very poor sense of direction…it was thirty years before the distinction between left and right had become visceral to me, and before I had acquired the art of reading a map’. So he wanders. And he sees the ragpicker sorting through rubbish and says about the ‘ragpicker and poet: both are concerned with refuse’. He writes of the Lost and Found office – the Fundbüro – where the detritus of the city is washed up, where its randomness is seen in the juxtapositions of odd objects. He notices that children are ‘irresistibly drawn to debris’, to finding and salvaging parts of the world. What is disregarded? What can be salvaged?

... |