Artist's Books / Special Editions

Almond, Darren: All Things Pass

Almond, Darren / Blechen, Carl: Landscapes

Brown, Glenn: And Thus We Existed

Butzer, André: Exhibitions Galerie Max Hetzler 2003–2022

Chinese Painting from No Name to Abstraction: Collection Ralf Laier

Choi, Cody: Mr. Hard Mix Master. Noblesse Hybridige

Demester, Jérémy: Fire Walk With Me

Dienst, Rolf-Gunter: Frühe Bilder und Gouachen

Dupuy-Spencer, Celeste: Fire But the Clouds Never Hung So Low Before

Ecker, Bogomir: You’re NeverAlone

Elmgreen and Dragset: After Dark

Förg, Günther: Forty Drawings 1993

Förg, Günther: Works from the Friedrichs Collection

Galerie Max Hetzler: Remember Everything

Galerie Max Hetzler: 1994–2003

Gréaud, Loris: Ladi Rogeurs Sir Loudrage Glorius Read

Grosse, Katharina: Spectrum without Traces

Hatoum, Mona (Kunstmuseum

St. Gallen)

Eric Hattan Works. Werke Œuvres 1979–2015

Hattan, Eric: Niemand ist mehr da

Herrera, Arturo: Boy and Dwarf

Hilliard, John: Accident and Design

Horn, Rebecca / Hayden Chisholm: Music for Rebecca Horn's installations

Horn, Rebecca: 10 Werke / 20 Postkarten – 10 Works / 20 Postcards

Huang Rui: Actual Space, Virtual Space

Kowski, Uwe: Paintings and Watercolors

Mikhailov, Boris: Temptation of Life

Mosebach, Martin / Rebecca Horn: Das Lamm (The Lamb)

Neto, Ernesto: From Sebastian to Olivia

Oehlen, Albert: Mirror Paintings

Oehlen, Albert: Spiegelbilder. Mirror Paintings 1982–1990

Oehlen, Albert: unverständliche braune Bilder

Oehlen, Pendleton, Pope.L, Sillman

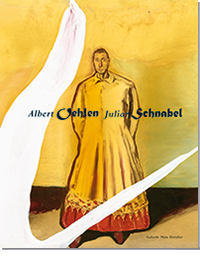

Oehlen, Albert | Schnabel, Julian

Phillips, Richard: Early Works on Paper

Riley, Bridget: Paintings and Related Works 1983–2010

Riley, Bridget: The Stripe Paintings

Riley, Bridget: Paintings 1984–2020

Roth, Dieter & Iannone, Dorothy

True Stories: A Show Related to an Era – The Eighties

Wang, Jiajia: Elegant, Circular, Timeless

Wool, Christopher: Westtexaspsychosculpture

Zhang Wei / Wang Luyan: A Conversation with Jia Wei

|

|

|||

Albert Oehlen | Julian Schnabel English / German

|

Since the 1980s, from both sides of the Atlantic, the artists Albert Oehlen and Julian Schnabel have continually questioned and reinvented painting with the help of conceptual strategies, an open approach to style, and a surprising use of found materials. They have been friends for three decades, and now, at a 2018 exhibition at Galerie Max Hetzler Berlin, they interconnect their current artistic positions and their shared past. Beside large-format canvases and smaller works on paper, the two present portraits they made of each other: Albert Oehlen in an oversized, ecclesiastical-looking frock in a positively baroque painting from 1997, and Julian Schnabel in strictly gray hues lounging on a couch, painted specifically for the occasion. In his new paintings shown here, Oehlen reworks the forms and colors he first used in his early abstract work of the mid-1980s with an evolved easiness of invention. Schnabel at that time started painting on used tarpaulins, and here again he collects found fabric, painting on the covers for market stands in Mexico. These bring their own specific marks and stories, over which the artist adds large gestural forms that evoke landscapes, flowers, or figures. An essay by art historian Christian Malycha elucidates this special meeting of minds, while painter Glenn Brown delivers a veritable declaration of love for the work of his two colleagues.

TRUST, DOUBT, FRIENDSHIP Vastness. And unseizable depth. A wall-like painting, more than three metres high and more than five metres wide. Rigorously barged into any gaze just like a billboard. Though mounted in blunt monumentality, the image remains elusive. In all its directness it is ambiguous and it takes a certain distance to see the drifting, seemingly boundless pink, into which one is practically thrown, for what it really is. The rosy ground consists of four vertically sewn widths of cloth. Partially scraped and dented, with several long dry stains. The whole cloth appears to be old and withered. And it neither reveals its descent nor the origins of the obvious signs of use and environmental effects. Julian Schnabel did not paint these colour grounds, he ‘selected’ them. The sunburned cloth comes from Mexico. He discovered it at a small market in Zihuatanejo on the Pacific coast, where it was used as a cover for the stalls and thus exposed to the elements. As Schnabel has told Sarah Cascone for Artnet, he likes ‘to work on dirty things’. Not for the dirt’s own sake but for ‘all of these little nuances’ of which ‘the history of the object’ is comprised, for the ‘time and place’ a painting ‘brings with it’ and which by this means are always told as well, on every painting. Thus, the pink is anything but abstract or non-objective. It is a thing, it has a history, its own colourous weight, so to say, its own shape. The pink is corporeal, far more than mere incarnate, and figural in itself. Schnabel inscribes himself into this given order. And almost effaces it. Onto or against the precise geometry of the vertical cloth widths he places an enormous figure. A blue diagonal cross, protruding from the lower left and upper right, spread in pastose oils. In addition, two single baulks of colour are brought into position, a massive one in chalky white on the right side as well as a blue one left of the painting’s lower centre. By a hair’s breadth, albeit most precisely, they are off the geometric structures. The signs do not come out even…

... |