Artist's Books / Special Editions

Almond, Darren: All Things Pass

Almond, Darren / Blechen, Carl: Landscapes

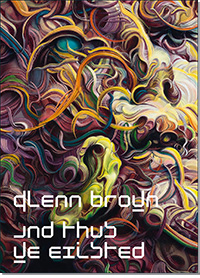

Brown, Glenn: And Thus We Existed

Butzer, André: Exhibitions Galerie Max Hetzler 2003–2022

Chinese Painting from No Name to Abstraction: Collection Ralf Laier

Choi, Cody: Mr. Hard Mix Master. Noblesse Hybridige

Demester, Jérémy: Fire Walk With Me

Dienst, Rolf-Gunter: Frühe Bilder und Gouachen

Dupuy-Spencer, Celeste: Fire But the Clouds Never Hung So Low Before

Ecker, Bogomir: You’re NeverAlone

Elmgreen and Dragset: After Dark

Förg, Günther: Forty Drawings 1993

Förg, Günther: Works from the Friedrichs Collection

Galerie Max Hetzler: Remember Everything

Galerie Max Hetzler: 1994–2003

Gréaud, Loris: Ladi Rogeurs Sir Loudrage Glorius Read

Grosse, Katharina: Spectrum without Traces

Hatoum, Mona (Kunstmuseum

St. Gallen)

Eric Hattan Works. Werke Œuvres 1979–2015

Hattan, Eric: Niemand ist mehr da

Herrera, Arturo: Boy and Dwarf

Hilliard, John: Accident and Design

Horn, Rebecca / Hayden Chisholm: Music for Rebecca Horn's installations

Horn, Rebecca: 10 Werke / 20 Postkarten – 10 Works / 20 Postcards

Huang Rui: Actual Space, Virtual Space

Kowski, Uwe: Paintings and Watercolors

Mikhailov, Boris: Temptation of Life

Mosebach, Martin / Rebecca Horn: Das Lamm (The Lamb)

Neto, Ernesto: From Sebastian to Olivia

Oehlen, Albert: Mirror Paintings

Oehlen, Albert: Spiegelbilder. Mirror Paintings 1982–1990

Oehlen, Albert: unverständliche braune Bilder

Oehlen, Pendleton, Pope.L, Sillman

Oehlen, Albert | Schnabel, Julian

Phillips, Richard: Early Works on Paper

Riley, Bridget: Paintings and Related Works 1983–2010

Riley, Bridget: The Stripe Paintings

Riley, Bridget: Paintings 1984–2020

Roth, Dieter & Iannone, Dorothy

True Stories: A Show Related to an Era – The Eighties

Wang, Jiajia: Elegant, Circular, Timeless

Wool, Christopher: Westtexaspsychosculpture

Zhang Wei / Wang Luyan: A Conversation with Jia Wei

|

|

|||

Glenn Brown: And Thus We Existed English

|

In Glenn Brown’s works, the paint takes on a life of its own. Brushstrokes become swirling interwoven bands of color that loosely circumscribe figures, dissolve them into surrealist mirages, and tie them back together. In Brown’s drawings it is the free-floating line that often superimposes two or three figures to describe the “schizophrenic self.” In his sculptures, the paint grows into space: brushstrokes flee the plane into a third dimension, threatening to smother the antique bronze figurines they climb over. In all of his work, Brown starts from models of earlier artworks, but today he says: “Much of the more rigid, photo-realist process I employed recently is gone.” In the new works the figures are alienated, mutilated, digitally manipulated, covered with seething color gradients. Brown actively works with the history of painting, draws on Raphael, Boucher, Delacroix, Baselitz—artists whose very personal manners inspire him to take new liberties. The book presents works from a double exhibition at Max Hetzler in Berlin and a show at the Musée National Eugène Delacroix in Paris. An essay by art historian Dawn Ades illuminates Brown’s strategies of appropriation and their parallels to surrealism or the spiritist painting of Georgiana Houghton. The artist himself offers deep insights into his approach and the development of the new work in a lengthy conversation.

THE ART OF PAINTING AND APPROPRIATING ART Glenn Brown’s earlier appropriated sources were flaunted: paintings by Dalí were meant to be recognised, as was Farnk Auerbach’s early painting style. Borrowings from popular culture, especially science fiction, invoked the new problem of copyright. Brown still always starts from pre-existing images. He favours the work of 17th- and 18th-century artists, finding it ‘more engaging, attractive, surreal and strange’ than contemporary art, but scours a very wide range of sources from the history of art. He doesn’t conceal them and is perfectly conscious of the roles of both appropriation and drawing – taken in its larger sense of disegno, encompassing drawing, composition and design – in the long history of oil painting and the revival of the classical tradition in the Renaissance, practices linked in theory at least since Giorgio Vasari. ‘Seeing that Design, having its origins in the intellect, draws out from many single things a general judgement, it is like a form or idea of all the objects in nature.’ Disegno is an activity of the mind, the acquisition of the knowledge of form in its philosophical sense, and was traditionally set against the ‘loose reliance’ on colour. Drawing is the first stage of discovering the ‘ideal’ form, not to be found in nature in a raw state. Joshua Reynolds advised the artist to aim for an ‘ideal beauty’ that is superior to ‘individual nature’: ‘The whole beauty and grandeur of the art consists, in my opinion, in being able to get above all singular forms, local customs, particularities and details of every kind.’ In the last gasp of a tradition in which appropriation was simply part of artistic practice, Reynolds laid out the correct steps for the apprentice painter: ‘An artist should enter into a competition with his original, and endeavour to improve what he is appropriating to his own work. Such imitation is so far from having anything in it of the servility of plagiarism, that it is a perpetual exercise of the mind, a continual invention.’ These encouraging statements for the students at the Royal Academy were underpinned by the presumption that ‘ideal beauty’ resided in the general, not the particular. In a deliberately grotesque application of logic to the notion of a visual ‘ideal’, Georges Bataille argued that if beauty only resides in a generalised form in which all local irregularities have been suppressed, the individual must be a deviation. He instanced an experiment which demonstrated that a composite face, built up from the superimposition of many individual faces, is as beautiful as the Hermes of Praxiteles. ‘The composite image would thus give a kind of reality to the necessarily beautiful Platonic idea.’ In this case the common measure that defined beauty would be dependent on the classical ideal. But whatever the ‘common measure’, every individual would necessarily, by definition, deviate from it: ‘Every individual form escapes this common measure and is to some degree a monster.’ Where do Brown’s appropriations and re-inventions lie in this once-contested arena? ‘Nature’ doesn’t really come into it. In some ways what Brown does with appropriation is the opposite of Reynolds – he particularises his borrowings, and could emphasise their original character, as he does with Rembrandt and Jan Lievens, or counters and transforms it. Many of the sources for his paintings are drawings of heads, and these seem quite often to belong to the generalised, classical ideal. Among the sources for The Crystal Escalator in the Palace of God Department Store are two Raphael heads of an Apostle and of a Muse, whose features do look smoothed into an ideal classical beauty, like the 17th-century chalk sketch of Alexander the Great that contributed to Black Ships Ate the Sky. But Brown re-fashions the Raphael heads after a contemporary stereotype, the flowing hair and red lips of glamour familiar on screen and in popular magazines. Look carefully at the eyes, though, and at the lips – we read these features into paint marks that are doing something else altogether than describing a mouth or eyelashes. Even so, the gender identity of the heads is ambiguous…

... In collaboration with Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin | Paris | London |