Künstlerbücher / Special Editions

Almond, Darren / Blechen, Carl: Landschaften

Brown, Glenn: And Thus We Existed

Butzer, André: Exhibitions Galerie Max Hetzler 2003–2022

Chinese Painting from No Name to Abstraction: Collection Ralf Laier

Choi, Cody: Mr. Hard Mix Master. Noblesse Hybridige

Demester, Jérémy: Fire Walk With Me

Dienst, Rolf-Gunter: Frühe Bilder und Gouachen

Dupuy-Spencer, Celeste: Fire But the Clouds Never Hung So Low Before

Ecker, Bogomir: Man ist nie Alone

Elmgreen and Dragset: After Dark

Förg, Günther: Forty Drawings 1993

Förg, Günther: Werke in der Sammlung Friedrichs

Galerie Max Hetzler: Remember Everything

Galerie Max Hetzler: 1994–2003

Gréaud, Loris: Ladi Rogeurs Sir Loudrage Glorius Read

Grosse, Katharina: Spectrum without Traces

Hatoum, Mona (Kunstmuseum

St. Gallen)

Eric Hattan Works. Werke Œuvres 1979–2015

Hattan, Eric: Niemand ist mehr da

Herrera, Arturo: Boy and Dwarf

Hilliard, John: Accident and Design

Horn, Rebecca / Hayden Chisholm: Music for Rebecca Horn's installations

Huang Rui: Actual Space, Virtual Space

Kowski, Uwe: Gemälde und Aquarelle

Mikhailov, Boris: Temptation of Life

Mosebach, Martin / Rebecca Horn: Das Lamm

Neto, Ernesto: From Sebastian to Olivia

Oehlen, Albert: Spiegelbilder. Mirror Paintings 1982–1990

Oehlen, Albert: unverständliche braune Bilder

Oehlen, Pendleton, Pope.L, Sillman

Oehlen, Albert | Schnabel, Julian

Phillips, Richard: Early Works on Paper

Riley, Bridget: Gemälde und andere Arbeiten 1983–2010

Riley, Bridget: Die Streifenbilder 1961–2012

Riley, Bridget: Paintings 1984–2020

True Stories: A Show Related to an Era – The Eighties

Wang, Jiajia: Elegant, Circular, Timeless

Wool, Christopher: Westtexaspsychosculpture

Zhang Wei / Wang Luyan: Ein Gespräch mit Jia Wei

|

|

|||

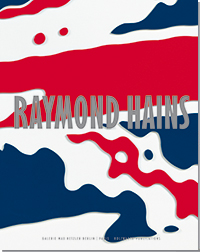

Raymond Hains Englisch / Französisch Hardcover mit 3 Ausklappseiten 24 x 30 cm 230 Seiten 176 Farb- und 42 Sw-Abbildungen 978-3-935567-82-4 50,00 Euro |

Der französische Künstler Raymond Hains (1926–2005) war Zeit seines Lebens ein unermüdlicher Neuerer, der in seiner Kunst immer wieder zeitgemäße Ausdrucksmittel und neue Chiffren fand. Bereits in den frühen Nachkriegsjahren experimentierte er mit Fotogrammen und optisch verzerrenden Kameralinsen in der von ihm so genannten hypnagogischen Fotografie. In den 1950er-Jahren holte er abgerissene Poster von den Plakatwänden der Städte, erklärte sie zu Gemälden und offerierte als Affichist eine realitätsnahe Alternative zur Spiritualität des abstrakten Expressionismus. 1960 gehörte er zu den Gründungsmitgliedern des Nouveau Realisme und brachte mit Bauzäunen die sperrige Wirklichkeit der Straße in den Ausstellungsraum. Dann entdeckte er die Möglichkeiten des Sprachspiels und hielt die sich ergebenden Narrationen und Gegenüberstellungen in Fotografien fest oder sammelte die dazugehörigen Dokumente in Koffern. An den Rändern des Stadtbilds entdeckte er Skulpturen auf der Straße, die er ebenfalls fotografierte. Um die Jahrtausendwende schließlich begann er seine Serie der Macintoshages, für die er Bilder auf den Dialogfenstern seines Computers collagierte, und formte Neonskulpturen nach den borromäischen Knoten des Psychologen Jacques Lacan. Diesem Erfindungsreichtum und der Vielschichtigkeit des Werks angemessen, zeigte die Galerie Max Hetzler 2015 eine thematisch angelegte Retrospektive gleichzeitig an allen drei Orten der Galerie in Berlin und Paris. Die vorliegende Publikation, als erste umfassende Monografie in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Estate des Künstlers geschaffen, spannt von dort einen größeren Bogen. Sie verdeutlicht die vielen Bezüge, die es in ihrer Gesamtheit ermöglichen, dieses künstlerische Schaffen in all seinen Verflechtungen zu erfahren. Dem kenntnisreichen werkbiografischen Essay von Kurator Jean-Marie Gallais sind eine persönliche Würdigung der Künstlerin Tacita Dean sowie ein Text und ein langes Gespräch mit dem Künstler von Hans Ulrich Obrist beigestellt, in dem Hains’ unerschöpfliche Assoziationsketten in seinen eigenen Worten nachlesbar werden.

THE RAVISHING OF TORN POSTERS AND THE REVERBERATIONS THEREOF In 1949, while filming shorts in the street, Hains’s eye strayed to a wall covered with posters. The inscription generally found on stretches of windowless wall in France thus gave his film its title: Loi du 29 juillet 1881 ou Défense d’afficher (Law of 29 July 1881 or Billposting forbidden). Hains photographed parts of this strangely stratified wall of paper, then decided to detach a fragment and take it home. The critic Alain Jouffroy gives a contextualised version of this hypothetical ‘first’: ‘The decision to consider torn posters as works of art dates back…to 1949, and coincided with a walk that Raymond Hains was taking in Saint-Germain-des-Prés…spotting a torn poster on the bottom of the rue de Rennes on a construction fence…he experienced what Zen Buddhists call satori: the torn eye of a woman made it possible to see the letters of the poster beneath. He unpeeled the poster and told Villeglé about it. Villeglé was then in Nantes…and immediately adopted the same procedure in the same derisive spirit, making fun of the abstract or semi-figurative painting then being done, which afforded, it must be said, singularly little interest compared to the discoveries of the pre-war painters.’ This foundational gesture, which brought together Hains, Villeglé, François Dufrêne (who exhibited the backs of posters), Mimmo Rotella and Wolf Vostell, marked a turning point in the history of art. Showing torn posters gathered in the streets had at least one thing in common with Marcel Duchamp’s readymades: pre-existence. But, whereas the readymade awarded a central place to its inventor (the person who chose the industrial object), the torn posters were the work of a multitude of anonymous passers-by. They did away with the notion of a creator and were the product of the city itself, realising the utopian idea of a collective work created ‘by everybody and not by Hains’ (or ‘by one’: in French, Hains is pronounced like un = one). The ‘collective unconscious’ was the Holy Grail of the Surrealists, which they located in the work of outsider artists. Now the affichistes had come up with a new definition of the collective unconscious, one that involved direct contact with city life and history. In another significant displacement, torn posters were the reverse of collage or assemblage, two emblematic procedures of modernity: décollage, in the most literal sense a rip-off – but also a take-off. Nevertheless, the first examples of posters harvested by Hains and Villeglé are clearly compositions made with deliberately torn and partly re-glued poster scraps. For Ach Alma Manetro (1949), Villeglé says that they shared the work of re-composition: the left-hand side was by Villeglé and the right-hand by Hains. In subsequent years, it was not unusual for the two artists to very lightly retouch their trouvailles... In Paris in the late 1950s, everyone was talking about the posters. But Raymond Hains took evasive action and over the next few years developed new approaches. Starting in 1957, he became interested in the metal supports to which the posters were stuck. The slender sheets of galvanised steel that he was soon purloining allowed him to escape the predominance of graphics or text characteristic of posters and to highlight abstraction. ‘When I began to be known, I took an interest in posters on galvanised steel [tôle]. Because I like this metal – its rust, the evocative power of its drawings, the dark stains (a little like foreign landscapes seen from a satellite). But most of all because a style had been found for me, in which, for the sake of irony, I let myself be confined.’ Galvanised steel allowed him to free himself of the notion of décollage. But the most important step in freeing Hains from his affiliation with torn posters was taken in 1959, ten years after his first experiments with poster-ripping. During the Paris Biennale at the Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris, in the so-called informels (informal artists) room, whose ceiling François Dufrêne had covered with a gigantic torn and reversed poster, Hains exhibited an imposing wooden palisade barrier that he had nicked from a construction site. The Palissade des emplacements réservés (Barrier reserved for billposting) goes still further than the tôles; formal aspects now took second place. By exhibiting a construction barrier, Hains was adopting a conceptual no less than a visual stance: the primary function of these wooden planks was, in that context, symbolic and metaphorical. From the outside, the palisade prevents one from seeing, hides an activity, and requires a deviation. Hains is telling us that we must look between the planks to see what (construction) works are hiding behind them. By making a show of a barrier, the artist reveals that art is elsewhere. The palisade, undeniably ‘the star of this Biennale’ for the press and critics, was takenby many to be a joke if not indeed a provocation. Other artists took the trouble to compose a manifesto asking that the museum should not become ‘a palisade-dump’ – a situation that Hains revelled in, passing the manifesto through his Hypnagogoscope to render it illegible. In 1968, Pierre Restany contextualised Hains’s gesture in his text on ‘The Invention of the Palisade’: ‘Invention is a mode of cognition, a style of perceiving and understanding things, and as such unlimited (or rather, its limits coincide with those of the world). The myth of the invention of the palisade symbolises this cosmic vision in Raymond Hains. The entire world is a picture and the palisade (of spaces reserved for bill posting) is not a painting but all painting at one’s fingertips.’ This invention was a turning point in Hains’s oeuvre, not least because it paved the way for a different system of thought and creation, the key to which was language. During the Biennale, he discovered in a shop window a recipe for Les entremets de la palissade (Palisade sweets) – he served this dessert during several dinners and action-spectacles from 1960 on – and subsequently met Madame de Chabannes La Palice, a descendant of Seigneur de La Palisse (La Palisse is a village in the département of Allier); to the Seigneur we owe the comical truisms known in French as lapalissades, which Hains decided to take very seriously indeed. And thus, in the Salon Comparaisons of 1960, he exhibited not a construction barrier but a reproduction of the Entremets de la palissade on a display case. This transition anticipated the more conceptual approach taken in his work from the 1960s onward...

... |