Artist's Books / Special Editions

Almond, Darren: All Things Pass

Almond, Darren / Blechen, Carl: Landscapes

Brown, Glenn: And Thus We Existed

Butzer, André: Exhibitions Galerie Max Hetzler 2003–2022

Chinese Painting from No Name to Abstraction: Collection Ralf Laier

Choi, Cody: Mr. Hard Mix Master. Noblesse Hybridige

Demester, Jérémy: Fire Walk With Me

Dienst, Rolf-Gunter: Frühe Bilder und Gouachen

Dupuy-Spencer, Celeste: Fire But the Clouds Never Hung So Low Before

Ecker, Bogomir: You’re NeverAlone

Elmgreen and Dragset: After Dark

Förg, Günther: Forty Drawings 1993

Förg, Günther: Works from the Friedrichs Collection

Galerie Max Hetzler: Remember Everything

Galerie Max Hetzler: 1994–2003

Gréaud, Loris: Ladi Rogeurs Sir Loudrage Glorius Read

Grosse, Katharina: Spectrum without Traces

Hatoum, Mona (Kunstmuseum

St. Gallen)

Eric Hattan Works. Werke Œuvres 1979–2015

Hattan, Eric: Niemand ist mehr da

Herrera, Arturo: Boy and Dwarf

Hilliard, John: Accident and Design

Horn, Rebecca / Hayden Chisholm: Music for Rebecca Horn's installations

Horn, Rebecca: 10 Werke / 20 Postkarten – 10 Works / 20 Postcards

Huang Rui: Actual Space, Virtual Space

Kowski, Uwe: Paintings and Watercolors

Mikhailov, Boris: Temptation of Life

Mosebach, Martin / Rebecca Horn: Das Lamm (The Lamb)

Neto, Ernesto: From Sebastian to Olivia

Oehlen, Albert: Mirror Paintings

Oehlen, Albert: Spiegelbilder. Mirror Paintings 1982–1990

Oehlen, Albert: unverständliche braune Bilder

Oehlen, Pendleton, Pope.L, Sillman

Oehlen, Albert | Schnabel, Julian

Phillips, Richard: Early Works on Paper

Riley, Bridget: Paintings and Related Works 1983–2010

Riley, Bridget: The Stripe Paintings

Riley, Bridget: Paintings 1984–2020

Roth, Dieter & Iannone, Dorothy

True Stories: A Show Related to an Era – The Eighties

Wang, Jiajia: Elegant, Circular, Timeless

Wool, Christopher: Westtexaspsychosculpture

Zhang Wei / Wang Luyan: A Conversation with Jia Wei

|

|

|||

Rebecca Warren English |

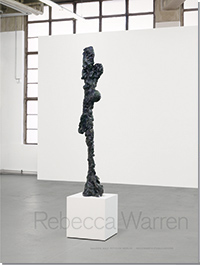

The focus of this book lies on a series of hand-painted bronzes which Rebecca Warren made in 2012. With their rough surfaces the elongated figures might remind you of Giacometti’s existential personage, but on closer look the references multiply, making Jörg Heiser of Daisy Duck, Sigmund Freud or Amy Winehouse in his essay. The works also take part in the gender discourse right down to the male- or female-connoted sculptural materials and techniques. To truly visualize all these aspects, the books shows four views of each sculpture, from every side on a spread, which renders each fingerprint kneaded into the form, each painterly effect in the hand coloring in fine detail. A triptych of make-shift vitrine displays collecting a tableau of studio detritus as well as cube sculptures from unfired clay that look like empty, worn-down pedestals round out this stringent selection of works.

BRONZE HEADS AND HAIR BOWS Rebecca Warren’s recent series of seven sculptures are like stalagmites built not from minerals and salt, but from a plethora of archetypes, clichés and inventions, both ancient and contemporary, shaped into perplexing new form by the artist’s hands. They have been sculpted in clay around a metal armature, then cast in bronze and hand-painted with car veneer to appear reminiscent of glazed ceramics. Roughly human-sized, their outline is slender and commanding at first (as well as a stalagmite, you might also think of a magnified tin soldier), yet some elements stick out like sore thumbs, or rather like bent elbows or bulbous noses or, in fact, like singular silicon breasts. The sculptures are placed on plinths, each coloured a different pastel hue, that are (purposefully and awkwardly) a little too modest and small to fulfil the plinth’s classical role as guarantor of distinction and authority. Meanwhile, the sculptures themselves have undulating surfaces that feel at once amorphous (like the skin of a thickly magmatic brew) and haptic (shaped by the artist’s hands, with imprints of the fingers’ tips and the hand’s gripping palm). With these qualities of shape and material all combined, these works make me think not only of stalagmites and tin soldiers, but also of Alberto Giacometti, Etruscan statues, Daisy Duck and Minnie Mouse, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Sigmund Freud, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Amy Winehouse, Marisa Merz, Auguste Rodin and Medardo Rosso... Take, for example, Toto (2012), one of the seven slender sculptures. Apart from a large triangular element, reminiscent of Giacometti-esque sideways-pointing breasts, a big bulbous nose or a bent elbow, protruding from what could thus be read as the torso of the figure, there is also a hair bow stuck prominently on top of its (narrow, heavily contorted) ‘head’. While the rest of the bronze is covered in hues of terracotta and cyan, the hair bow is blotched in old rose and pistachio, emphasizing the composite rather than unified aspect of the piece. The hair bow is a returning motif in Warren’s work (see, for example, the voluptuous clay female figure Pony from 2003, which features a hair bow on top of its head like a boudoir pillow). It is a perfect shorthand code for cartoon female role models courtesy of Disney. Both Daisy Duck and Minnie Mouse sport huge hair bows that strongly differentiate them from their male hero counterparts Donald and Mickey. Warren pits these simplified cartoonist patterns of gender against the equally simplified, but pronouncedly ‘serious’ patterns that the male-dominated history of modernism has to offer. This experimental, slapstick collision of Giacometti and Disney, literally cast or pressed into one physical body, leaves neither unharmed. In fact Warren’s sculpture could be read as a response to culturally entrenched gender tropes – the slender modernist outline on the one hand, and the Disneyish codification of cuteness and effervescence on the other hand – colliding in the real world, in real people’s lives. Think of the late Amy Winehouse: big breast implants and anorexia; Warren does not merely make illustrative comments by pitting two things against each other, however. There is more at play. Sticking two things together that ‘don’t fit’ is just one possible method. Another is to duplicate (while twisting the logic of duplication); another, to alter proportion (elongate, squeeze etc.). And yet another is to use materials and conventions in unconventional ways. Think of Winehouse again: the postmodern mixture of visual styles and the clear modernism of Soul music.

... In collaboration with Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin

|